Scenic Rivers - A Partnership to Protect Rivers

A Partnership to Protect Rivers, by Becky Rideout, is reprinted from the South Carolina Wildlife magazine, May-June 1995.

Motor nearly idling, the pontoon boat edges closer to the riverbank. A narrow drainage ditch comes into view, camouflaged by small trees and leaf litter. We strain forward to get a better look at the trickle of water flowing into the Lynches River. Jack Moore leans back in his seat and shakes his head. "I don't know if this is where the problem is coming from. I just know that I don't catch fish here like I used to," he tells me.

Motor nearly idling, the pontoon boat edges closer to the riverbank. A narrow drainage ditch comes into view, camouflaged by small trees and leaf litter. We strain forward to get a better look at the trickle of water flowing into the Lynches River. Jack Moore leans back in his seat and shakes his head. "I don't know if this is where the problem is coming from. I just know that I don't catch fish here like I used to," he tells me.

A Lake City businessman, Moore has lived on the Lynches for many years. He has spent countless lazy afternoons pulling redbreast from the water and observing the serene beauty of the river as it flows silently past tall pines and moss-draped cypress. In recent years, however, Moore has noticed changes in and along the river: more houses, talk of new industry and sewage treatment plants, and more people to share the river on a pretty Saturday morning. Sometimes after a heavy rain, the water is murky with sediment. And the big ones don't seem to be biting in certain old fishing holes.

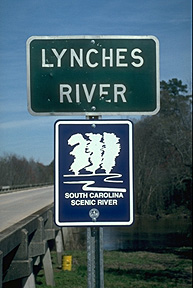

Moore is not alone in his admiration and concern for the Lynches. His upstream neighbors are hard at work to protect the fishery, prime wildlife habitat, lovely vistas, and water quality of the Lynches River through a partnership with the South Carolina Scenic Rivers Program. The partnership provides an opportunity for river-bordering landowners like Jack Moore and other folks in the local community to work with the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) on a plan to safeguard the river for today and in the future.

The Scenic Rivers Program, administered through the DNR's Water Resources Division, is charged to protect unique and outstanding river features. Through a community planning approach, the program identifies and prioritizes resources for protection, including plant and animal life, wildlife habitat, wetlands, scenic views, geologic formations, recreation areas, and cultural or historic treasures. Local people working together to create a vision for their river landowners, fishermen, boaters, birdwatchers, farmers and loggers, businesses, and other folks who are "just interested" that's what the Scenic Rivers Program is all about.

Long-term river management requires foresight, hard work, and dedication on the part of a community. First, someone (an individual or group) must ask DNR to include the river in the S.C. Scenic Rivers System. In response, program staff study the river to determine if it is eligible for scenic status. The study considers the natural, scenic, and historic/cultural resources of the river as well as landowner and community support for the designation.

Long-term river management requires foresight, hard work, and dedication on the part of a community. First, someone (an individual or group) must ask DNR to include the river in the S.C. Scenic Rivers System. In response, program staff study the river to determine if it is eligible for scenic status. The study considers the natural, scenic, and historic/cultural resources of the river as well as landowner and community support for the designation.

During the eligibility study, a classification is determined for the river. A river may be classified Type I (Natural), Type II (Scenic), or Type III (Recreational) depending on the level of development in the river corridor. "Scenic river" is a general term that applies to all three river types. The Scenic Rivers Program has developed voluntary land and water management guidelines for each classification.

Characterized by undeveloped shorelines and pure water, Type I rivers are wild in nature and can be reached only by trail or water. A natural river is also free-flowing which means there are no dams, diversions, or riprap to change the flow patterns. Natural rivers are found in wilderness settings an untouched mountain cove or a deep swamp forest. The shoreline of a Type II river may be more developed with limited road access. Activities that do not affect the natural character of the river such as farming and timber management are common on Type II rivers. In fact, the scenic classification can help protect traditional agricultural and silvicultural uses. The Type III (Recreational) classification allows for urban and suburban rivers to be protected through the program. As the name implies, the appeal of a recreational river lies in good fishing and boating.

Of course, you can't have a scenic river without a special resource, whether it's the site of the last duel in South Carolina, a series of rugged whitewater rapids beckoning the adventurous kayaker, or an endangered lily that puts on a brief, beautiful display in springtime.

However, it takes something more to keep a river scenic: the human resource. That is why the most important aspect of the eligibility study is determining whether the river-bordering landowners and the local community support scenic status for their river.

Barry Beasley, Manager of the Scenic Rivers Program, "We absolutely will not proceed with a scenic designation without community support. If a river is going to be protected, the local people must be involved. The reason is simple the quality of the resource depends on how riparian landowners and river users manage their land and water activities. Do they farm and log to the river's edge or do they leave a vegetated buffer to hold soil in place and act as a filter? Do boaters and fishermen respect the resource or do they leave trash and trespass on private property? There are many more questions I could pose. The point is that many river issues can't be solved by government. On a state-designated scenic river, DNR supplies technical expertise and guidance to help a community be a better caretaker of its river."

If a community favors scenic designation, the next step is to gain the approval of the county council(s). Then, after building local support, program staff seek official approval for the scenic designation from the state General Assembly and the Governor. Once the designation is final, a never-ending process to protect the river begins.

Soon after the official designation, the Director of DNR appoints a ten-member advisory council to guide development of a river management plan. The council, chaired by DNR staff, is made up of people who live in the community and know the river. A majority of the council must be riparian landowners. Building a council of ten people with different backgrounds, ideas, and interests is a major goal of the Scenic Rivers Program, because such diversity allows for consideration of the broad spectrum of opinions within a community.

The recently established Lynches River Advisory Council provides a good example. The council is focusing on a 54-mile segment of the Lynches from US 15 near Bishopville to the eastern boundary of Lynches River State Park in Florence County. At a November 1994 kick-off meeting, council members expressed their reasons for taking part in the project, and the reasons were diverse. William Kelly, a young landowner and founding member of the local river protection group behind the scenic designation, urged the council to keep the river free of pollution, "God created this river, and it doesn't belong to anyone. We need to keep it clean so my children and grandchildren can enjoy it," he says. Tres Hyman, a landowner and forester by trade, added his hope that the designation will result in stewardship of the land and water, "We need to establish a riparian buffer with management guidelines to protect the river."

But there are other concerns to be taken into account. If landowners agree to voluntary management guidelines, will they forfeit private property rights? Thomas Gosski, a Lee County landowner, believes the council must consider the interests of private landowners. As council member Howard Vincent put it, "The river needs to be preserved for recreational use, but the plan must also allow for other uses such as timber management."

Jack Moore and his concerns about fishing on the Lynches must also be heeded. That is just one of the many questions the Lynches River Advisory Council will have to consider as it works to develop a plan for the river. What makes the Lynches a special river worthy of protection? What areas or resources most need protection and why? What types of activities are occurring on the river? How might those activities affect the river today and in the future? What role can private landowners play in protection of the river? What are the local people willing to do to keep the Lynches a special river worthy of protection?

Once a plan is written, the next step is to put the plan into action. On a scenic river, implementation of the management plan is intended to last forever. Although the faces may change over time, there will always be a council to revisit issues, consider new problems, and plan for future management of the river as long as river protection remains a top priority of the river community.

The Lynches River is the newest addition to the Scenic Rivers System. Management plans have already been developed and are in effect for four other rivers in the state: a fifteen-mile stretch of the Broad River in Cherokee and York counties; the lower 14 miles of the Little Pee Dee; a tenmile segment of the lower Saluda below Lake Murray; and about five miles along the middle Saluda in northern Greenville County. One fact stands out as advisory councils for these scenic rivers implement their plans: The scenic river designation in and of itself does little to protect a river. A long-time member of Trout Unlimited and the Federation of Fly Fishers, Malcolm Leaphart of the Lower Saluda River Advisory Council has learned this lesson firsthand.

"The scenic designation does not carry land or water use regulations to force appropriate management of a river," he says. "Instead, scenic status provides a forum where all the players can meet, discuss issues, and plan for the future. In remembering our successes on the lower Saluda, I think back to the mid-1980s when the advisory council helped defeat a proposed sewage treatment plant that would have overloaded the river harming water quality and fisheries. The council promoted a regional sewer system which is finally becoming a reality." Issues currently being addressed by the Lower Saluda River Advisory Council include possible portage routes around a dangerous set of rapids and support for development of a regional riverfront park.

On the Broad River in Cherokee County, life unfolds at a slower pace and the issues are somewhat different than on the lower Saluda. A retired school teacher and member of the Broad River Advisory Council, Joan Wheeler tells of progress on the Broad. "Our biggest accomplishment so far has been preventing a dam that would have flooded 20,000 acres and disrupted the river and lives of folks in the community. Now, we are starting to work one-on-one with landowners along the river to encourage everyone to take care of their own. We don't want to take control of the land. We just want to keep the area in its present state. If one person allows wholesale development of their riverfront property, it will change the character of the river for everybody."

Land management options available to riparian landowners through the Scenic Rivers Program range from a non-binding, voluntary land management agreement to granting of a conservation easement. The bottom line is that protection requires commitment. To truly protect a river and its resources, landowners and river users must look beyond their own lifetimes.

More than 11,000 miles of rivers flow through South Carolina from the rollicking whitewater of the upstate to the meandering blackwater streams of the coastal plain. As of January 1995, almost 98 miles along the Broad, Little Pee Dee, lower Saluda, Lynches, and middle Saluda rivers were included in the Scenic Rivers System. Work is moving forward to add another 38 miles on the Little Pee Dee. The Scenic Rivers Program is challenged to protect outstanding river resources while providing for industrial and economic development.

Barry Beasley asserts, "We can't expect to 'save' every river, but we can help local people protect some of the most special places." Numerous potential scenic rivers flow through our state; perhaps one in your own back yard.

For information on ways to protect it, write:

S.C. Scenic Rivers Program

SC Department of Natural Resources

P.O. Box 167

Columbia, SC 29202

803-734-9096

email: marshallb@dnr.sc.gov