DNR News** Archived Article - please check for current information. **

Shorebird research underscores importance of South Carolina beaches June 7, 2018

Every red knot caught by SCDNR researchers, including this bird released in 2017, sports a set of tags that will allow it to be identified if re-sighted anywhere else in the hemisphere. (Photo: Ed Konrad)

Every spring, thousands of small, robin-sized shorebirds descend on South Carolina beaches. They arrive in light gray plumage, feasting first on coquina clams and then nutrient-dense horseshoe crab eggs. By the time they leave, hopefully refueled, they’re sporting the rosy breeding feathers for which they’re named.

Red knots make astounding migrations each year from wintering grounds at the southernmost tip of South America to nesting grounds north of the Arctic Circle, stopping at beaches along the way to rest and refuel.

Ongoing research by South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) biologists has begun to highlight the particular significance of South Carolina beaches in these migrations – with data showing that as many as two-thirds of the birds here fly directly to the Arctic after leaving our beaches.

“We now know that for some shorebirds, South Carolina is the last stop to gain weight or energy for their journey to the Arctic,” said SCDNR bird biologist Felicia Sanders, who leads the agency’s research on red knots.

South Carolina has long been known as a spot to find red knots in the early spring, along with numerous other shorebird species, including dunlin, ruddy turnstones, whimbrels and sanderlings. Traveling from distant wintering grounds – as far flung as Brazil and Tierra del Fuego in South America – their ultimate destination is the high Arctic, where they nest each summer. Along their migration route, the Arctic-nesting shorebirds concentrate in large numbers at sites to refuel – and one of these stopover sites is South Carolina.

During late winter and spring, red knots gather by the thousands along South Carolina beaches, especially at Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge and Seabrook, Kiawah, and Harbor Islands. At times, they form the largest flock on the Atlantic Coast, with as many as 8,000 knots counted on Kiawah Island in recent years. During February and March, the flock builds in size as more birds fly in from southern wintering areas. Here, the amazing migrants rest, feed and prepare for their northward migration. They also feed to fuel the growth of breeding plumage after they molt their winter feathers.

In early spring, knots eat small Donax clams, also known as coquinas. These saltwater clams live in the sand on beaches in high concentrations. When the water warms to approximately 68 degrees Fahrenheit, another food source becomes available: horseshoe crab eggs. During the new and full moon tides of April and May, female horseshoe crabs come to bays and inlets along South Carolina’s coast to lay eggs in the sand. The eggs are energy-rich and easily digestible, making an ideal food source for shorebirds. Red knots and other shorebirds disperse from their large flocks in April and May and search out horseshoe crab spawning sites.

Over the last few decades, red knots have declined by nearly 85%. This drastic decline led to the red knot receiving federal protection under the Endangered Species Act in 2015. Disturbance and food availability, especially during migration, are suspected reasons for the drop in numbers.

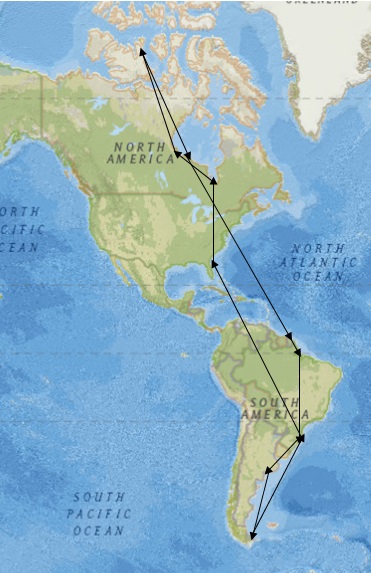

This image, a collaborative effort between SCDNR, Ron Porter, Larry Niles, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, shows the one-year migration path of a red knot. This bird was captured in South Carolina in 2016 on Deveaux Bank and a geolocator was affixed to its leg. During the life of its transmitter, the bird traveled 2x to its nesting grounds above the Arctic Circle and 2x to its wintering grounds in Tierra Del Fuego, Chile at the southern tip of South America. The bird was captured again in January 2018, and the geolocator was retrieved.

Since 2010, SCDNR biologists have conducted research on red knots to understand the role that South Carolina plays in these birds’ journeys. Researchers and volunteers have captured hundreds of knots, measuring them them and placing field-readable engraved bands on their legs. These unique markers on each bird allow biologists to track individual birds if they are re-sighted anywhere in the hemisphere. Documenting how South Carolina’s resources are being utilized by red knots may help efforts to conserve this vulnerable species.

Biologists with SCDNR and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in partnership with Dr. Larry Niles, Ron Porter and many volunteers, have also placed geolocators on some of the captured knots. Geolocators are small, electronic devices that measure and record light levels to determine global location. Geolocators are a valuable tool to study bird migration routes and identify staging areas, although birds must be re-captured to obtain the data from the devices.

In spring 2017, SCDNR staff began using another new technology to track 20 red knots. Nanotags are very small radio transmitters that emit a unique pulse that can be detected by Motus towers. Bird researchers have erected these towers along migration routes, and tagged birds are thus recorded as they pass. Unlike geolocators, nanotag data can be obtained immediately, providing migration information without having to recapture the birds.

Together, location data from the geolocator and nanotag projects are already yielding unexpected results, suggesting that two-thirds of the red knots in South Carolina may fly directly to the Arctic after leaving our beaches. Previously, South Carolina beaches were assumed to be one stop among many along the Atlantic coast for these birds. That drives home the importance of an adequate supply of food such coquina clams and horseshoe crab eggs in South Carolina.

“All of this information identifies South Carolina beaches as very important for red knot and other shorebirds’ survival,” Sanders said.

Best Practices for Sharing the Beach with Shorebirds

- Avoid disturbing birds and causing them to fly.

- Respect roped-off nesting areas.

- Follow leash laws and keep dogs out of sensitive bird habitat.

DNR Media Contacts

| Area | Personnel | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Coastal | David Lucas | 843-610-0096 |

| Marine | Erin Weeks | 843-953-9845 |

| Midlands | Kaley Nevin | 803-917-0398 |

| Upstate | Greg Lucas | 864-380-5201 |

After Hours Radio Room - 803-955-4000